Unveiling the Shadows of Nairobi’s Sex Economy

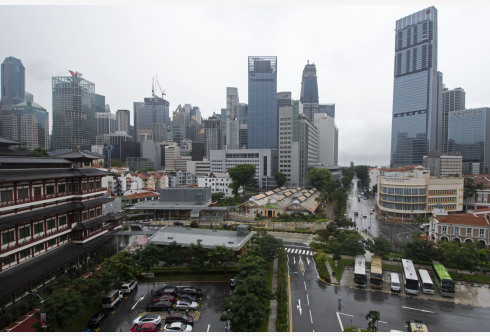

Nairobi,

Monday, 27 January, 2025

McCreadie Andias

In the heart of Nairobi, as dusk falls and the city’s relentless hum gives way to softer echoes, another rhythm takes over. Neon lights flicker above downtown clubs, matatus hustle commuters home, and the city begins to exhale its daytime tension. For many, this marks the beginning of their rest.

For others, it is the start of their workday—work that thrives in the shadows and ignites fiery debates across societal divides. Nairobi’s sex work industry is an open secret, a paradox of discretion and ubiquity, survival and stigma, defiance and desperation.

This is the story of the women, men, and nonbinary individuals who navigate this complex world, the clients who fuel it, and the policymakers who grapple with it. It’s a kaleidoscope of resilience, exploitation, liberation, and economics, unfolding beneath the glare of the city’s harsh inequalities.

Meet Ciku, a 27-year-old mother of two who operates in Westlands, Nairobi’s affluent entertainment district. Draped in a bold red dress that exudes confidence, she leans against a lamppost, scanning the street for potential clients.

“I didn’t choose this life,” she begins with a shrug. “But when my marriage ended, and I had no job, what else could I do? My kids have to eat, and school fees don’t pay themselves.”

Ciku’s story is echoed by Patricia, 45, who works in the less glamorous parts of River Road. “Here, it’s survival of the fittest. I’ve been doing this for over 20 years.

I’ve seen it all—the good days, the bad days, the dangerous ones. What keeps me going? My three kids, who are now in college. They don’t know how I make money, and I want to keep it that way.”

On the other side of the transaction is Dennis, a 32-year-old tech worker who frequents Nairobi’s high-end escorts. “There’s a lot of judgment around men who pay for sex,” he confesses.

“But it’s not always about the act. Sometimes it’s about companionship, someone to talk to after a long day.” His admission highlights an often-overlooked facet of the industry: it’s not always about sex.

Sex work in Nairobi is as varied as the city itself. In upmarket areas like Kilimani and Lavington, high-class escorts charge upwards of Ksh. 20,000 a night, catering to wealthy businessmen, expatriates, and politicians. Meanwhile, in low-income areas, the rates can drop to as little as Ksh. 100 for a quick transaction.

But the industry isn’t limited to street corners and hotel rooms. Social media platforms like Instagram, Tinder, and Telegram have revolutionized the trade, with sex workers branding themselves as “luxury companions” and offering curated experiences to an exclusive clientele.

“Technology has made things easier and safer for us,” says Eva, a 24-year-old university student who moonlights as a call girl. “I can vet my clients online and avoid those who seem sketchy. Plus, the pay is better because I cut out the middlemen.”

In Kenya, sex work exists in a legal grey area. Prostitution itself isn’t illegal, but related activities such as solicitation and brothel-keeping are criminalized. This ambiguity leaves sex workers vulnerable to exploitation by law enforcement.

“Police officers are our biggest threat,” says Jane, who works in the heart of Nairobi’s CBD. “They’ll arrest you, take your money, and sometimes even demand free services in exchange for letting you go.”

Advocates for sex workers’ rights argue that decriminalization could address these issues. “Criminalizing sex work only pushes it further underground, making it more dangerous,” says Dr. Njeri Mwangi, a sociologist specializing in gender and urban studies.

“If we want to protect these workers, we need to create an environment where they can report abuse without fear of arrest.”

Experts have long debated the social and economic impacts of Nairobi’s sex industry. Dr. Samuel Ochieng, an economist, views it as a symptom of broader structural inequalities. “When you have unemployment rates as high as 12% and an informal economy that accounts for 83% of jobs, people will do whatever it takes to survive,” he explains.

Meanwhile, Pastor Grace Kamau, a vocal opponent of sex work, sees it as a moral crisis. “We have lost our values as a society. These young women need guidance, not condemnation. The church must step in to offer alternatives.”

Public opinion on sex work remains deeply divided. While some see it as a legitimate form of labor that should be regulated, others view it as a moral failing that must be eradicated. Yet, amid this polarized debate, the voices of sex workers themselves are often drowned out.

“I don’t need pity or judgment,” says Ciku. “What I need is respect and the chance to live my life without fear.”

Her sentiment is echoed by many others who see sex work not as a choice, but as a means to an end—a way to navigate the harsh realities of life in a city where the cost of living continues to skyrocket.

As the first light of dawn breaks over the city, the streets begin to clear. The night workers retreat to their homes, blending back into society until the next evening. Their lives, like Nairobi itself, are a tapestry of contrasts—strength and vulnerability, despair and hope, invisibility and resilience.

The question that remains is not whether Nairobi’s sex industry will persist—it will—but how society will choose to engage with it. Will it continue to criminalize and stigmatize, or will it embrace a more nuanced, compassionate approach?

What's Your Reaction?