Meet Pacilisa Wanyonyi who has mastered the art of Baking With Millet Flour

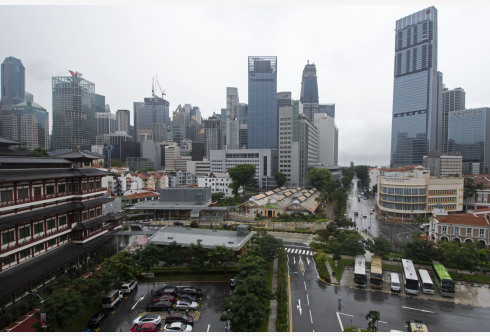

Nairobi,

Wednesday July 19, 2022,

KNA by William Inganga

Though her real name is Pacilisa Wanyonyi, she’s popularly known as Mama Wimbi in Osia village in Teso South, Busia County where she lives.

Her nickname is a pointer to her passion. She’s been pursuing her career with zeal knowing that it makes her eke out an honest living through the modest financial returns that she gains.

Every morning, from Monday to Saturday, draped in her overalls, she ferries specific utensils from her permanent house to a tin-walled bakery that’s partially covered and therefore well ventilated. The bakery is within the same compound as her house.

A stainless steel oven stands in the bakery and seems to be silently waiting for the time that it will be put to use. Besides, a traditional firewood stove appears dormant, but not for long. It will come alive after hot charcoal embers have heated the oven. These precede the mixing of Mama Wimbi’s ingredients.

Mrs. Wanyonyi does value addition to millet flour. Her ingredients are wheat flour, baking powder, sugar, vanilla, grated lemon, eggs, and salt. She's mastered the correct proportions of mixing. “The ratio of wheat to millet flour is 2:1,” she says. Depending on the desired outcome, a 1:1 ratio is also an option,” she adds.

Wheat flour appears smooth to the eye and between fingers. However, Mama Wimbi doesn’t assume. She measures one moderate cup of wheat flour. She thoroughly sieves it. “Wheat flour usually has some coarse substances,” she says.

“When baking cakes, those particles could be a nuisance in the mouth. Here are the particles,” she says, after completing the sieving. Next to be filtered is the millet flour which settles in the same container with the wheat flour. “It’s ground at a local miller and so it has to be sieved for better quality,” mama Wimbi adds.

The particles from the millet are coarser than those from the wheat flour. Two spoonful of the whole grated lemon are sprinkled onto the flour compound followed by three spoonful of baking powder and a pinch of salt.

The most obvious sweetener is sugar. The quantity varies depending on the preferred outcome. Using a tablespoon, Mama Wimbi stirs four whole eggs mixed with some sugar in a plastic container. The beating continues until the abrasive crystalline feel in the container is considerably diminished.

She takes a break from the egg beating to mix the two flours and the grated lemon, using a wooden cooking stick. She returns to beating the eggs. She measures six caps of vanilla into the egg and sugar solution. She resumes the beating. She realizes that she hadn’t mentioned one liquid that’s in a cup.

“This is lemon juice,” she says. She sieves it to restrain the seeds. She measures four tablespoons of the lemon juice into the egg solution. The stirring continues.

One of her employees joins her. Mama Wimbi says, “She’ll make chapatti from wimbi flour.” She assures this writer and those accompanying him, “You’ll leave this place satisfied. There are cakes, chapattis, and porridge, which you should begin taking," she says justifying the reason for her statement, “You’ve visited a bakery and so you shouldn’t stay hungry.”

Had we known that this kind of hospitality was awaiting us, we wouldn’t have taken breakfast at our hotel.

Mama Wimbi’s 19-year-old daughter, Pauline Ndeda, joins her. While Mum gently pours the egg solution into the mixed flours, Ndeda does the kneading. The dough stiffens. A little water is intermittently added between kneading.

“When I was in school, I loved home science because of my mother,” Ndeda says adding: “I was interested in things cookery.” However, she was not taught how to prepare millet-based dishes and her mother has filled that gap.

Ndeda discloses that home science is the subject she performed best. "I had a plain A," she says revealing she desires to pursue a hospitality course in college as she loves cooking.

Mama Wimbi lifts some of the dough with the wooden stick. The dough gently streaks into the trough. “If the dough is thick, the results won’t be good,” she says.

The last ingredient is a generous scoop of margarine. The final stirring gels the dominantly brownish compound with the yellow margarine. A fine paste is produced. But wait a minute!

Mama Wimbi tells her daughter to continue with further smoothening. Meantime, Mama Wimbi cleans the aluminum baking trays to be used. She coats the inside of the trays, the bottom, and the sides, with a film of liquid cooking oil. “If you don’t do this, the cake will stick onto the tray.”

The process here sounds like a relay, albeit a confectionary one. Mother takes over. She smoothly releases the paste into the two trays. One is round and the other square-shaped. A metallic spoon is used to plaster the top of the dough in each tray. The oil forms the boundary between the dough and the inner walls of the trays.

By this time, the charcoal embers in the oven are partially teetering black and orange as they glow. They have reached a state that can heat the temperature in the oven for the right baking.

Mama Wimbi's oven has four layers of racks. The two trays are slipped into the oven. Square one goes into the third level while round one on to the second. “You put them where you want,” she says.

She shuts the doors of the oven. “I’ll check after 40 minutes,” she says. Following a similar process as earlier described, another mound of dough is made. This is for mandazis. To bridge the time before the cake is ready, Mama Wimbi seizes this opportunity to narrate her story.

After forty minutes, she opens the oven’s doors. She slips a knife into one cake and then the other. “They are not yet quite ready,” she says. “Parts of the cake shouldn’t stick onto the knife.”

A charcoal stove is panning chapattis while the traditional firewood concrete stove has been fired up. Oil is being heated in readiness for the preparation of mandazis.

After a few more minutes, the knife for measuring the level that the cake has baked is slipped into the cakes. This time, they pass the test. The pans are carefully retrieved from the oven, hands safely padded with a cloth to avoid scolding.

The aromatic smell confirms that indeed this is a bakery. The cakes are let loose onto plates. One of them is cut into pieces. Each visitor is handed a hot, steaming piece. Nods affirm how tasty the cake is.

One two-kilogram packet of wheat flour produces 27 chapattis for Mama Wimbi. But blending the two types of flour, gives her almost double, depending on the chosen ratios.

Having completed preparing the variety of millet foods, Mama Wimbi lays a table. Included, are millet bottled crackies that had been made earlier. A thermos of wimbi flour porridge is also inviting.

Under normal circumstances, nutritionists will likely frown at one sinking his teeth into several layers of a folded millet chapatti and washing it down with a gulp of millet porridge. Itchy hands scouring the surface of a millet cake would also be yearning to chip off a piece. Roaming eyes may not have ignored the millet crackies and the palate could go demanding a share.

But this is sampling. After all 2023 is the International Year of Millets. The millets must prove that they are desirous of recapturing the glory they had when our grandfathers thrived on them. Mama Wimbi's table hasn't disappointed.

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT—Spanish acronym) Partnerships and Seed Systems Lead under the dry land crops program is Dr. Chris Ojiewo.

He says, “There is hidden hunger. You don’t see somebody hungry because the person has a full stomach. But the individual is missing on micronutrients that are important for the body’s development.”

A Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO)) food scientist, Dr. Francis Wayua, says, “For a long time, millet has been promoted as food for the sick, the elderly and the young.” This attitude, ‘stigmatizes’ the crop considering how underutilized it is.”

The micronutrients Dr. Ojiewo is referring to are Iron, Zinc, and selenium among others, which are critical in ensuring proper health that curbs mental retardation.

Rather than take such micronutrients as supplements in the form of tablets or capsules, Dr. Ojiewo recommends having the intake via millet foods.

If people were to consume more millet, Dr. Ojiewo believes that multiple solutions about nutrition, health, education, and national development would be more easily tackled.

Dr. Ojiewo recognizes that several millers are using millet and sorghum to blend maize. “Even if they blend it with 10, 20 percent, that is huge,” he says adding: “If 100, 50 or even 80 percent of Kenyans would consume that maize blended with millet, the market base will be so huge that the farmers are likely to make a lot of money from millet production.”

Mama Wimbi is proud to have a 'presidential snack' since former President Uhuru Kenyatta tasted her crackies during a food festival at the Kenyatta International Convention Centre a few years ago.

Her earnings have enabled her to assist her husband, a teacher, in educating their children and meeting the cost of other expenses.

Courtesy K.N.A

What's Your Reaction?